BACKGROUND

With the passage of its National Parks and Nature Reserve Ordinance 1998, Sarawak had devoted to drastic protection of natural habitat, flora and fauna species with the main mission for biodiversity conservation and at the same time to promote ecotourism. The emphasis on gazetting Piasau Camp as a nature reserve is for the simple reason that they are the chief means of maintaining intact natural ecosystems and preserving biodiversity in a city that is becoming increasingly urbanized.

Half of civilization lives in urban areas, in the cities of which the population are expected to rise annually. Due to this, access to natural habitat is a far catch to some who lives in the cities therefore nature parks in the city play vital role in human wellbeing through providing access to nature (Maller et al., 2009).

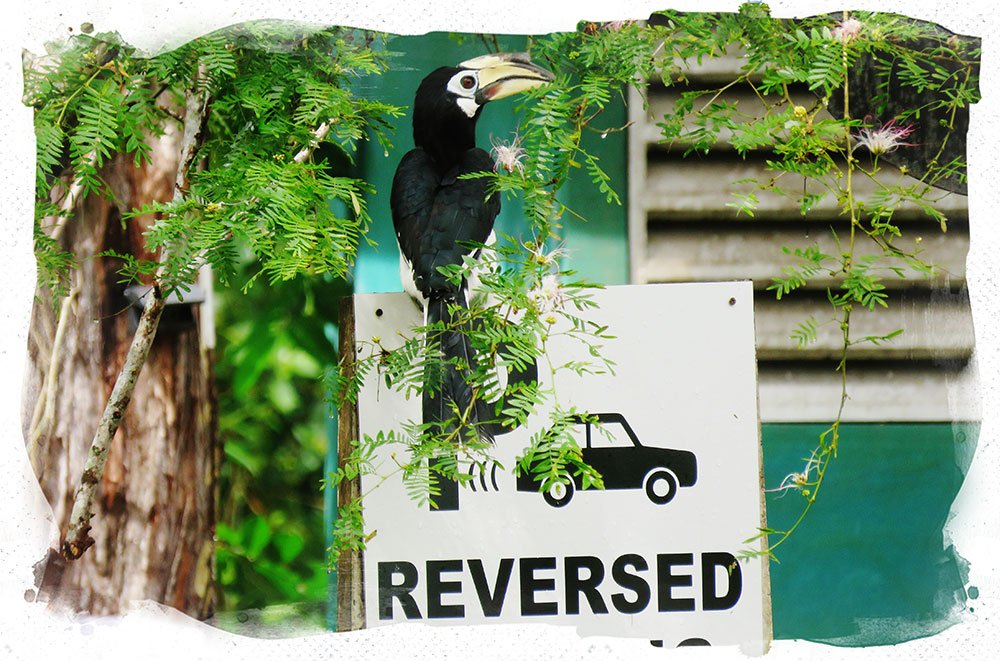

Piasau Nature Reserve (PNR) is very important for the conservations of some components of biodiversity in particular Sarawak’s birdlife and threats to their existence. Therefore the reserve provide varied opportunities for Miri citizens to meet and interact in both formal and informal settings; most importantly, an avenue for generations after generations to appreciate our diverse birdlife and in particular the breeding pair of Oriental Pied Hornbill (OPH).

It is challenging to help people living in the cities, who are only familiar with pigeons, sparrows and crows to understand the intrinsic value of these ancient birds and the threats they are facing

The accessibility of PNR as an urban green space is a good encouragement for Miri city residents to be in nature. PNR is to be created into a beautiful place in the city providing a healthy setting for people to observe and encounter animals in their natural environment. PNR too provide convenient access to bird watch as part of the people’s recreational activities. Bird watching was found to be the fastest growing recreational activity (Cordell et al., 1999). This activity had gained immerse popularity among the residents of Miri and became the backbone of eco – tourism activities in PNR.

Aside from bird watching and other recreational activities, PNR may provide peoples in and around Miri city opportunity to access a natural space and to experience educational value of the vegetation types of the park and how these trees and forest have a symbiotic relations with the wildlife in the reserve. There are many additional benefits associated with urban forest that contributes to the long – term functioning of urban ecosystems and the well – being of urban residents (Nowak, 2007). Urban forest like PNR can act as reservoirs for endangered species in a highly populated and urbanized Miri city.

Experiences that are sought – after are predominantly enjoying the natural scenery, peace and quietness (Tyrväinen et al., 2002) and the main highlight of every individual’s visit to PNR is to be able to watch the OPH family of four; Jimmy and Juliet, the breeding pair together with their young fledges Cecelia and Musa.

Different sections of societies in Miri tend to have a collective value regarding urban forest reserve like PNR which is the importance of the habitat for the well – being of bird population. Although a nature park like this seems desirable to many people but at the same time the city had become more compact and the needs for space had intensifies. Therefore it is crucial to emphasize on the multifunctional use of parks like PNR and draw attention of city dwellers towards the biodiversity of Sarawak’s wildlife in particular the birdlife and protection of their habitat.

The amazing story of the OPH pair with their offspring can be framed into a thematic interpretation that will definitely enhance the experience of visitors in the park. Since interpretation involves imparting knowledge, a visitor’s knowledge can be deepened and eventually an impact on their attitude (Ham, 2007). A corresponding impact on behavior is most likely able to contribute to a better protection of our hornbill habitat in PNR. When visitors to parks attain a satisfying experiences, they will be more receptive in supporting every park’s vision to sustainable management of natural habitat (McArthur, 1994).